Joppa, sometimes spelled Joppee, or Joppie, is Hebrew for “beautiful” or “new beginnings”, and is also the name of one of the Dallas’s few preserved freedmen's towns that remains today. Sitting just north of I-45 and Highway 12, it is nestled between the Trinity River and the Union Pacific rail lines, with the Great Trinity Forest just to the east and the Joppa Preserve to the south. The other side of the river has seen millions of dollars of investment in golf courses, an equestrian center and a neighborhood park expansion. Joppa is primarily shotgun houses that have stood in the neighborhood for generations. Currently, about 500 people live in Joppa

Land grant certificate granting Robinson F. Smith a portion of the land where Joppa is now located.

Texas Land Grant. Dallas, Texas: 1837. https://s3.glo.texas.gov/ncu/SCANDOCS/archives_webfiles/arcmaps/webfiles/landgrants/PDFs/3/3/7/337356.pdf

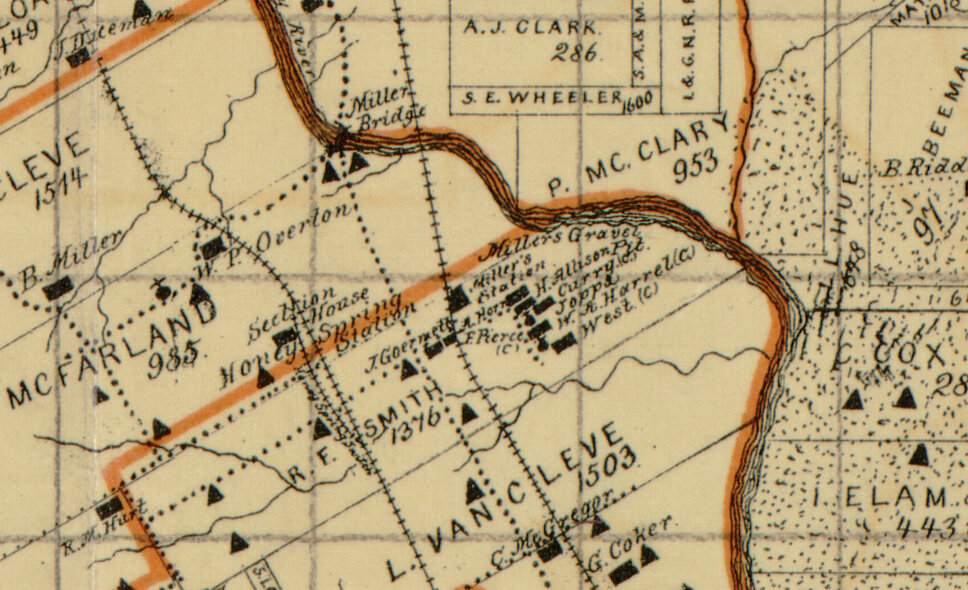

The land where Joppa currently sits was once inhabited by Native American tribes. When people of European descent colonized the area, they divided up the land, creating “land grants” transferring ownership of Native American land into private hands. The Joppa neighborhood is on land that was granted to Robinson F. Smith and Lorenzo Van Cleve, who were each “given” 800 acres of land in 1845, in exchange for their service in the Army of Texas. The surrounding area was also divided up amongst former soldiers of the Republic of Texas - just north of R.F. Smith survey was the Dugland McFarland survey, and north of that another Lorenzo Van Cleve survey. Over time, that land was further divided up amongst family and other colonizers.

Joppa area settled by freeman Henry Critz Hines

During the Civil War, southern white owners of enslaved people sought ways to ensure that enslaved people would not become free. While Texas was a southern state that upheld slavery, it did not see a lot of fighting or much presence from Union soldiers. Southern Confederates saw Texas as a potentially safe place to resettle, lay low, or send enslaved people until the war was over. Henry Critz Hines was an enslaved person sent as property from Missouri or Alabama to Texas for protection until the end of the Civil War. He was sent to the Miller Plantation, a plantation on the Lorenzo Van Cleve survey north of today’s Joppa. In addition to the Plantation, the Miller’s also ran one of a few local ferry companies that shuttled people across the Trinity. After the end of the Civil War and the declaration of the Emancipation Declaration, many formerly enslaved peoples who had been on the Miller Plantation stayed in the area. In the early 1870’s, the Houston and Texas Central Railroad was built, making its way north from Houston, reaching Dallas in 1872. It’s believed that it was around this time that Henry Critz Hines settled in Joppa. Historian Donald Peyton said in a 1991 Dallas Morning News article that “when the slaves were freed, Miller gave Hines the ferry which was used to cross the Trinity River. The railroad had been built and the ferry was becoming outdated. But Hines still prospered.” Soon after other formerly enslaved persons at the Miller Plantation or other East Texas plantations came and settled in the area.

Establishment of New Zion Missionary Baptist Church

Churches have always been an important part of the Joppa community. New Zion Missionary Baptist Church was founded in 1882 by Reverend and Sister Haverty, Deacon and Sister J. Floyd, and Deacon and Sister Pierce, at a home on the corner of Ervay and Colonial. The church relocated to its present location in Joppa in 1888. According to the New Zion’s current website “The church building once served as a schoolhouse, a temporary pediatric clinic for our children and a voting place for this precinct.” Gethsemane Missionary Baptist Church is known to be the second oldest church in the neighborhood.

It was around the time of the New Zion’s relocation to Joppa that the Missouri, Kansas, and Texas Railroad was constructed, arriving near Joppa in 1886 with Miller’s Station. While the area remained agricultural, the new local infrastructure brought increased development, including the establishment of Honey Springs, a nearby town settled around a H.&T.C. station of the same name. An article in the Dallas Morning News indicates that in 1888, Henry Critz, the founder of Joppa, was living in nearby Millers Switch. A 1930 article written by the grandson of W.B. Miller wrote that Critz continued to operate the Miller Ferry until 1890, when a flood washed out the landing. The Miller’s Ferry Bridge was built soon after, making the ferry service obsolete.

Early Dallas map showing homes, churches, and infrastructure. Street, Samuel M. Sam Street's map of Dallas County, Texas. Dallas, Tex.: Sam Street, 1900. Map. https://www.loc.gov/item/2005625344/

Families continued to make their home in Joppa. The Sam Street’s map from 1900 indicates that there were at least 7 families in that area at the time, including the Harrel’s, the Pierce’s, the West’s, the Curry’s, the Horn’s, and the Allison’s.

Mrs. Laura Belle Foster and Mr. P.H. Foster (center and left) and their family. Photo courtesy of Mrs. Delveeta Thompson, Mrs. Foster’s grand daughter, right.

Neighborhood Organizing

Over the coming decades more residents continued to settle in Joppa. Neighborhood organizer Laura Belle Foster (nee Davis) first moved to Dallas in 1924. After a time away to attend college in California, Mrs. Foster returned to Dallas for good, moving to Joppa when the South Central Expressway expanded and displaced her family and other residents in the Black neighborhood of Queen City. In addition to raising 2 children, she taught Sunday School at Mt. Moriah Baptist Church, was on the Board of Directors of the Dallas Negro Chamber of Commerce, served on the Board of Equalization for the Wilmer-Hutchins Independent School District, among many other civic commitments. Under the Dallas Negro Chamber and led by Mrs. Foster and her husband P.H. Foster, in 1948 the South Central Civic League was organized to fight for community programs and services, stating:

THE OBJECTIVES ARE AS FOLLOWS:

To get better bus services.

To get traffic signs for our schools.

To get better mail services.

Annexation to the city of Dallas

To get better sanitation for our community,

To get fire plugs for our safety

To get water for our community

Ms. Shalondria Jackson, current President of the South Central Civic League, shares a story about Melissa Pierce

Mrs. and Mr. Foster and their daughter made Joppa’s first street signs out of lumber they purchased, digging holes and installing them throughout the neighborhood.In addition to the fight for city services, Mrs. Foster and other residents fought for civil rights. Mrs. Foster's grand-daughter Mrs. Delveeta Thompson described that fight in her text “Joppa History Report”:

Many residents suchs as the Crowders, Lovely, Sorrells, Miles, Hosus, Blacks gathered together to support these efforts with their biggest battles for the school and the right to vote. Laura Belle has Commissioner Jim Tyson, Senator Oscar Mauzy, City Officials Mike McKool and Royce O. to assist in their right to vote and later assisted in getting our long established polling places at the oldest church, New Zion Baptist Church.

The Joppa area in 1930. Image courtesy of the City of Dallas

Joppa Schools

From when it was formed in 1927 until the district was dissolved in 1970, Joppa was in the Willmer-Hutchins Independent School District. Black students were not allowed to attend white schools and had to attend schools for Black students, which districts were not eager to build or invest in. For many years there was no official school building in Joppa. New Zion Baptist Church was used as a school, or students walked to another neighborhood, sometimes having to cross through dangerous conditions to get there. Mrs. Thompson described how Joppa’s school, the Melissa Pierce School, came to be:

My mother and my uncle, they ended up with a lot of students from this neighborhood having to walk the railroad track over into South Dallas. They used the church partly as a school for the community, but when my mother and uncles and those that grew up with them out here, were actually walking the train tracks, they were going to high school then would had asked Southern Pacific Railroad to hold the trains up during the time that all of the students from this community around my, my group, my mother and my uncles age would have to walk the tracks so that they could walk safely over and then they will stop the train so they could return safely back to the neighborhood. That really lit the fire, that there was a school that was needed in this neighborhood. So for my grandmother explaining it to me, then Ms. Melissa Pierce, knowing that this is what needs to be done. My grandmother rather went to the Wilmer Hutchins school board and asked them for a school. And of course in that day it was not going to happen, and it didn't happen. They did tell my grandmother, unless you come up with the land, we're not building your people a school at the time….Mr. Hitt was the superintendent and the president of Wilmer Hutchins school board. The building sat on Illinois not far from here. And my grandmother would get people together on their days off and sit under a couple of trees with pallets, what they call pallets, you know throw blankets of quilt and have lunch and sit in trying to get them to get them a church, a school, you know, or a building for them. Not not just to keep having it in the church, but to be actually able to have an official school building. So needless to say, when they did say buy the land and then we'll build it - my grandmother said put it in writing. You know, Ms. Melissa Pierce was present, so Ms. Pierce. told my grandmother: "Definitely I can donate the land." And so that's how it came about. All of the land for the school building as well as a football, baseball field so the kids wouldn't have to worry about not having enough room for those particular activities.

According to Mrs. Thompson, Melissa Pierce was a formerly enslaved person whose family acquired land after emancipation. The Sam Street’s Map has a Pierce family in Joppa, indicating they were one of the earliest settlers of the area. A 1948 Dallas Morning News article described a new 4-room brick building that would be built for Black students of the district, and would consolidate four segregated schools. The Melissa Pierce School was dedicated on September 28th, 1952. The City of Dallas’ National Historic Registry application for the Melissa Pierce School says that:

The building was constructed to accommodate grades 1-12 and those who attended the school recall that the smaller building contained the elementary grades. The classrooms in the larger building, with the attached gym/auditorium, were for middle/high school students. Two areas which were later added on for classrooms, one to the side of the gym and the other to the side of the smaller classroom building, have since been demolished.

Unlike white schools, the Melissa Pierce School started in October instead of September to accommodate local White farmers who wanted Black students to be available to pick cotton in the late summer. Parents didn’t want their children’s education to be interrupted. In 1954, the Dallas NAACP organized parents in the Joppee community to demand admission for students into the all-white school, Linfield Elementary. They were denied by the Principal of Linfield stating the Texas Education Agency called for segregated schools.

The Joppa area in 1940. Image courtesy of the City of Dallas

Joppa annexed into City of Dallas

In the late 1940s and 50s, the City of Dallas annexed a number of towns and unincorporated areas around Dallas. The nearby town of Honey Springs was annexed in 1946. Joppa was annexed into Dallas October 3, 1955. Despite being part of Dallas, Joppa continued to be part of the Wilmer-Hutchins school district. Joppa resident Edgar Green described his experience with being bussed to WHISD after grade-school:

I went to elementary and some junior high (at Melissa Pierce). Then finished my junior high at Bishop, Bishop Heights, and my high school and at Kennedy. I went, some of my elementary was, at the A.L. Morney down in Hutchins. You know, bussed, I was always bussed, but not to the white school, the black schools. Then when desegregation came, then they took some of the black kids to the white school and some of the white kids to the black school.

In 1970, facing potential federal prosecution for failure to integrate WHISD schools, the Wilmer-Hutchins ISD board adopted a plan to integrate the district by August of that year. Melissa Pierce School was “phased out”, with the lower grades sent to Wilmer and Hutchins elementary schools. The building was subsequently auctioned off in 1972. In August 1970, more than 1,000 white residents of the Wilmer-Hutchins district who were unhappy with the prospect of integration, fought for the annexation of southern Wilmer-Hutchins district into the nearby, mostly white, Ferris school system. The southern half of Wilmer-Hutchins was 90% white, while the northern half was 90% Black. In November of 1970, the motion was approved, Wilmer-Hutchins ISD was dissolves - the southern half of the school district was absorbed by Ferris ISD, and the northern half absorbed by Dallas ISD.

The Joppa area in 1962. Image courtesy of the City of Dallas

Ms. Claudia Denise Fowler shares a story about Ms. Charlie Mae Jackson

Infrastructure

The South Central Civic League continued to fight for improvements in the neighborhood. Up until the 1970s, residents would carpool to public transportation. The neighborhood organized to get bus service along Carbondale, which would take residents to the end of the Ervay Streetcar line in South Dallas, or to downtown. In an interview, Mrs. Delveeta Thompson describes the work of Mrs. Charlie Mae Jackson, who led the South Central Civic League from the 1990s to 2000s, to improve infrastructure in Joppa. A 1955 street map shows that the neighborhood was practically divided in half, connected only via Carbondale Street. Edgar Green describes the division: “Fosters crossing Honey Spring Branch - that's the river, the creek that runs through here, they called this Honey Springs. You know, believe it or not, before that you had to come out and go down Burma road and then go down here to Carbondale to go to the other side. We only had, you know, one way to get to the other side.” Mrs. Foster worked with residents to have a direct connection built between the two halves of the neighborhood. And on May 15, 1999, a plaque was placed near Gethsemane Missionary Baptist Church, declaring it “Foster’s Crossing” in dedication to South Central Civic League leaders Laura Belle Foster and P.H. Foster. Although Mr. Foster passed away before the project was complete, Mrs. Foster was able to see the street and travel Foster’s Crossing herself.

Foster’s Crossing wasn’t the only infrastructure improvement residents have fought for in recent years. For decades, crossing the train tracks at Linfield was the only way in or out of the neighborhood. Throughout its history, at-street-grade crossing of the trains proved not only a nuisance but a danger to Joppa residents. In the 1990s, residents organized to get bond funding from the City to build a bridge over the train tracks. Mrs. Delveeta Thompson wrote of the push for the new bridge:

This was due to the loss of many lives of loved ones needing an Emergency Medical Unit/Paramedics Assistance, but they were detained for long periods because a train moving 100 plus freight cars, switching freight cars or what we and our ancestors experiences as non-moving freight cars with a waiting period of 30 minutes to one hour and 45 minutes. Southern/Union Pacific showed no compassion nor have any regard to the life-threatening situations of husbands and wives, mothers and fathers, grandparents nor children and uncles/aunts.

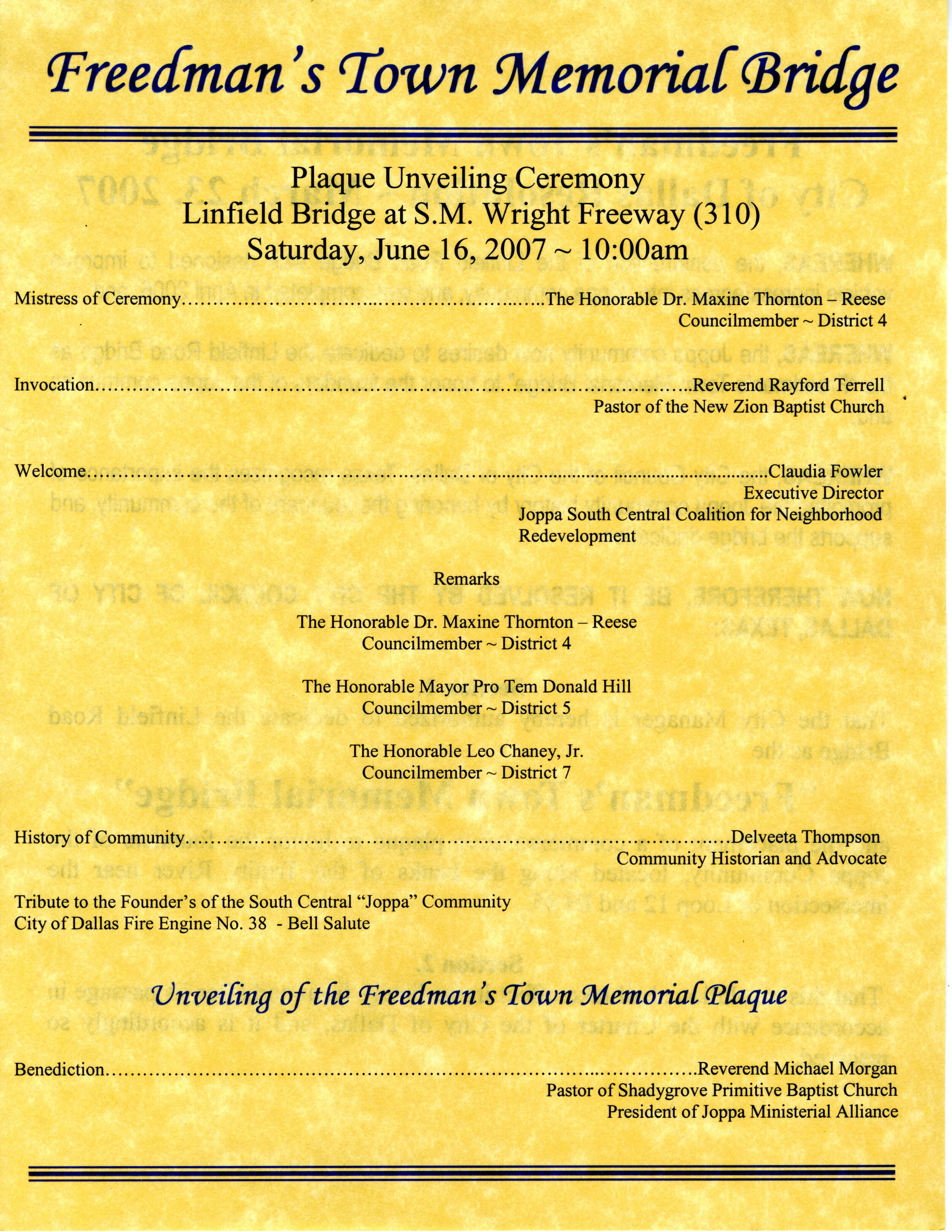

Program for the opening of the Linfield Bridge. Courtesy of Mrs. Delveeta Thompson

But the bridge project was delayed, faltering a few times until in 2007, the neighborhood celebrated the ribbon cutting ceremony of the Freedman’s Town Memorial Bridge, which provides another connection to Joppa, over the railroad tracks. And while the bridge was hard fought, some residents don’t feel that the solution fully addressed the problem.

I would have said that ain't wide enough, how are pedestrians supposed to get across it? I would have said that because it's common sense. But when people don't involve enough people or where people that might have some knowledge about some things that you might not have knowledge about - you don't get to pool all that knowledge together to come up with a good viable situation, a solution. And that's what I think happened to the bridge.

Program for the unveiling of the Joppee Historical Marker Ribbon Cutting Ceremony. Courtesy of Mrs. Delveeta Thompson

Joppa Today

In the past decade the neighborhood has continued to see change. Over 100 new homes have been built, bringing new residents to the area. While the Melissa Pierce School remains closed, residents would like to see it returned to a community use. Since there is no school in the community, students go to school at South Oak Cliff, Roosevelt, or other schools throughout Dallas. In 2015, South Central Park, with a gazebo and splash pad was opened. The following year the neighborhood celebrated the unveiling of its historical marker at the park. The South Central Civic League continues to operate to this day, fighting for the neighborhood. In addition to working toward building a community multipurpose center and putting in place a neighborhood stabilization overlay, fifth generation Joppa resident and current Civic League president Shalondria Galimore was a vision for the neighborhood:

What we're trying to do now is to further stabilize what we actually have and to preserve what we have now. We want to be at the table when economic development comes in to see what that looks like and what's best for the community. I think that we need mixed income in the community to help stabilize because Joppa will not be able to survive on the present income or the present voting role that we have actually at this time. We need to work with the companies that are around us that have been neighbors that have tried to be friendly neighbors, and to let them know what our thoughts and desires are and how they can help us attain or further sustain those goals that we have.

![[bc]](http://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5248ebd5e4b0240948a6ceff/1412268209242-TTW0GOFNZPDW9PV7QFXD/bcW_square+big.jpg?format=1000w)